Defending Against Advanced Threats

This post will cover strategies and tactical considerations for detecting advanced threats, with a focus on Detection Engineering.

Introduction

Threat actor capabilities and techniques have evolved and matured from simple, destructive malware written by individual authors at the dawn of the Internet era to the present, where teams of advanced threat actors persistently attack organizations to gain access to their networks and eventually meet their objectives.

The information security field has also continued to adapt to threat actors and their capabilities.

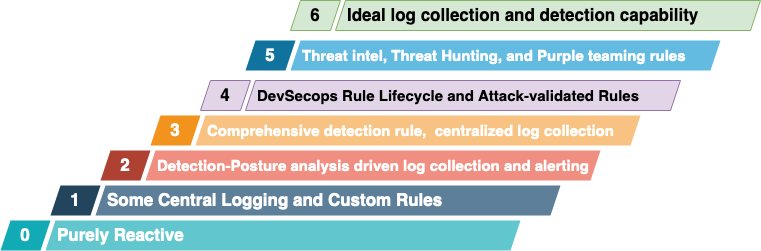

In this post, an approach on how a modern blue team (defenders) can prepare to detect and respond to Advanced Persistent Threats (APTs) is proposed. A capability-driven maturity model is also introduced, which allows security teams to measure attack readiness, establish goals, and measure progress with respect to their ability to detect APTs.

Lastly, a reference Detection Engineering lifecycle as well as a related Attack Simulation/Validation Detection-as-Code pipeline will be covered, where detection capability is continually tested against current detection rules and platforms.

What's happening out there?

With the exception of opportunistic and unsophisticated threat actors that are incorrectly granted the APT label, and regardless of the maturity of an organization's security team, APTs are rarely discovered and stopped at the early stages of their attack. Often, APTs are discovered some time after their initial intrusion, once they've established a foothold in the network and have moved on to credential discovery and/or lateral movement.

In 2020, Russian state-sponsored actors (APT29) were discovered by FireEye in their network after having used a software supply chain attack to compromise a SolarWinds deployment. Later, it was found out that these actors had compromised all sorts of organizations around the world that used this product.

In more recent years, Salt Typhoon have been prolific at targeting telecom providers worldwide, including lawful intercept systems used by US law enforcement. This gave them access to countless phone calls, SMS messages, and unencrypted network traffic. In most cases, the dwell time for Salt Typhoon has been measured in terms of years.

Within the last few years, ransomware gangs have become more mature and established; they are succeeding so much at compromising organizations that they, like defensive security teams, are starving for talent, to the point of offering hefty sign-on bonuses for anyone who will help them use existing access to corporate networks to move laterally and eventually deploy ransomware and exfiltrate data. The time to develop exploits on newly published vulnerabilities has also dropped rapidly in recent years, to the point where, within 24-48 hours after publication, threat actors have already reverse-engineered the patches and have begun exploiting vulnerable targets.

APTs are usually (but not always) teams comprised of talented individuals who continually hone their skills and improve their tradecraft to maximize their ability to evade detection (dwell time) before they achieve their objectives. After initial compromise, APTs typically use implants as tools where they manually interact with compromised hosts (hands-on-keyboard activity) and persistently figure out ways to advance through the network.

This is a stark contrast to less advanced threat actors whose attack strategy usually revolves around the scale of the attack. Even though all threat actors work to evade detections, less sophisticated actors have no critical need to bypass pricey security products or evade dedicated security teams. One reason is that, unlike APTs, they don't have resources they can commit to patiently and persistently adapting to their newly developed tools and techniques being discovered. Another reason for this is that they usually target such a wide variety of victims that it is nearly impossible to avoid being detected by several security products, who in turn share Threat Intelligence to disrupt the attack infrastructure. Similarly, post-exploitation for less sophisticated threat actors is typically an automated function, as opposed to a manual "hands-on-keyboard" function for more advanced threat actors.

Detecting Advanced Threats

By nature, advanced threat actors work hard to elude the security controls they can anticipate. This includes detection content such as Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR) rules, anti-virus signatures, Intrusion Detection System (IDS) rules, Threat Intelligence feeds, and Security Information and Event Management (SIEM) detection rules.

Strategies to Detect Advanced Threats

Threat Hunting

Threat Hunting is a discipline where hunters work to understand attacker techniques and search for hard-to-change tactical activity patterns, to find compromises that wouldn't or couldn't otherwise be detected by near-real-time detection rules.

Purple Teaming

Purple Teaming is a collaboration of defenders and red teamers. Roles, scopes, and other details might vary between organizations and objectives. However, all purple team engagements involve simulating threat actor activity and measuring the effectiveness of security controls, including detection content.

Threat Intelligence

Advanced threat actors can be detected by operationalizing Threat Intelligence efficiently. However, these threat actors cannot be discovered easily using indicators or attributes that are not costly for them to change. Most APTs are well-resourced, which means changing IP addresses, domains, hashes, and other similar attributes (see Pyramid of Pain) is not difficult for them.

A mature Threat Intelligence program will involve qualified analysts who will consume Threat Intelligence reports and work with other teams to disseminate prioritized and actionable intelligence. This means, for example, detection rules and Threat Hunting exercises can be optimized to focus on the most relevant threats against the organization. Incident responders, threat hunters, and detection engineers can focus on the most up-to-date tactical intelligence with the highest adaptation cost for threat actors, while automated detections can be optimized to operationalize low adaptation cost Indicators of Compromise (IoCs).

Detection Engineering

Both Threat Hunting and Purple Teaming are supposed to contribute to an organization's detection capability. Successful hunts should be converted into detection rules, as should missed detections from Purple Team exercises. The overarching goal of both disciplines is to reduce threat actor dwell time.

As a result, a mature organization capable of detecting advanced threats should not only have a mature Threat Hunting, Threat Intelligence, and Purple Teaming program, but it should also have a mature Detection Engineering program that integrates well with all of them.

At a high level, there are two means of detecting advanced threats: Threat Hunting and detection rules. The rest of this post focuses on Detection Engineering, which is the process and discipline of crafting and maintaining real-time detections.

Detection Engineering Maturity Model (DEMM)

When talking about an organization's capability to detect advanced threats, the dogma "A chain is as strong as its weakest link" is ever more relevant. This means an immature Detection Engineering program will severely reduce the team's ability to detect advanced threats. That is because even with a successful Threat Intelligence, Threat Hunting, and Purple Teaming program, it is real-time detections that can meaningfully reduce threat actor dwell time. In other words, Detection Engineering is at the front lines of the battle. Other measures can help in detecting APT compromises, but since they are not reacting to real-time events, they can't impact dwell time as effectively as detection content.

To measure a Detection Engineering program's readiness to detect advanced threats, a maturity model is proposed where seven levels of maturity can be measured, each representing a significant milestone that indicates a certain level of resources and commitment is required from threat actors if they are to evade detection by the organization's security team.

It is important to note that most of the capabilities listed can be outsourced to security vendors such as EDRs and Managed Detection and Response (MDR) providers.

DEMM-0 - Purely Reactive

At DEMM-0, the organization has little to no detection rules of its own. MDR providers may be monitoring the organization's logs; however, similar to installing EDRs on endpoints or enabling built-in IDS rules, the Detection Engineering capability of the organization itself is purely reactive.

"Reactive" in this context means the detection capability is only discovered when there are actual threats. Advanced threats are discovered long after their initial compromise, typically after they have acted on their objectives. Even when threats are detected early, if there are little to no central logging capabilities or proactive incident response planning, the eradication of threats is likely to prove ineffective against advanced threats.DEMM-1: Some Central Logging and Custom Rules

Organizations with this level of maturity have taken proactive steps to detect specific threats and centrally collect infrastructure logs that they consider important enough to monitor. However, the lack of sufficient and reliable logging and the immature stage of the Detection Engineering program means there is still a lot of work to be done before detecting advanced threats without relying on threat actors making a mistake becomes a realistic capability.

DEMM-2: Detection-Posture-Driven Log Collection and Alerting

At DEMM-2, security teams have completed an analysis of their detection posture, which should include missing or inadequate logs, capabilities (e.g., traffic decryption or EDR deployment coverage), or processes.

Both log collection and alerting are driven by an understanding of gaps advanced threat actors can abuse to evade detection.

While the detection capability of non-advanced threats should improve at this level, the resources and persistent nature of APTs would still mean additional maturity is needed before they can be detected.

DEMM-3: Comprehensive detection rules with adequate centralized data collection

At DEMM-3, detection rules have matured to the point that most well-known threat actor techniques can be detected. Log collection also includes application logs.

Vendor-agnostic logging and detection posture measures should also be established at this maturity level.

While not always possible, vendor-agnostic log collection means changes in SIEM, data-lake platform, and tooling due to business reasons or other factors will have minimal adaptation cost for the security team and won't dramatically reduce the detection posture as a result. This is important because all the investment and work put into developing maturity could be wasted if foundational components of Detection Engineering, such as log collection and rule content, are faced with instability and disruptions requiring redevelopment of lost capabilities. In other words, changes in vendors, platforms, and tooling happen, and a mature detection team must anticipate and be ready to adapt to such changes. Maturity cannot be achieved without stability.

At this level, reliably detecting some advanced threats is practical. Centralized data collection means other programs such as Threat Intelligence and Threat Hunting also have enough information about the environment to detect threats missed by detection rules.

DEMM-4: Detection-as-Code Rule Lifecycle and Attack-validated Rules

The maturity level achieved at DEMM-3 comes with certain assumptions, such as detection rules being functional, evasion scenarios threat actors might use being considered by rules, and logs collected being parsed in a way that is compatible with rule content.

At DEMM-3, broken, missing, or incomplete rules are detected incidentally or after a compromise happens. At DEMM-4, rules are validated using realistic Attack Simulations. Rules should also be subject to regular review and tuning.

A proper lifecycle should also be followed for detection rules to ensure only relevant and effective rules are alerting incident responders.

A Detection-as-Code approach is ideal to meet these goals. The DevOps discipline emerged in the software development industry to help address similar concerns of maturity, reliability, and collaboration that allowed software developers to rapidly release features while maintaining the quality of their software. The process of making a detection rule lifecycle process compatible with a DevOps process is called Detection-as-Code. Treating rule content as if it were code (which arguably, it is!) and integrating test validation—Attack Simulation/Validation or Breach and Attack Simulation (BAS) can be used interchangeably—into the process of Detection Engineering, much like how software engineering CI/CD pipelines integrate unit tests, allows security teams to rapidly release and tune rule content and thereby ensure their capability to detect advanced threats stays current with the latest threat actor capabilities, techniques, and trends.

Implementing Detection-as-Code in Detection Engineering means having a CI/CD pipeline that integrates Attack Simulations and attack validations to ensure configured rules can detect threats they are expected to detect, and that changes in rules, log availability, or platform availability do not silently affect the organization's capability to detect threats. Version control, rule standard compliance (to make rules easy to audit, integrate, and tune), and other processes needed to implement a mature Detection Engineering program should also be implemented as part of a Detection-as-Code pipeline.

At DEMM-4, the detection team should be measuring false positive rates and detection gaps, with a clear goal of minimizing the number of false positive detections and maximizing the number of true positive detections of threat actor activity. With metrics and measurements, it should be noted that understanding the underlying causes is the goal. Metrics should never be targets on their own.

Additionally, processes should be established to reactively as well as proactively consume feedback from incident responders about false positive rules as well as the quality of the detection content. Strategies to allocate detection engineer's time efficiently, such as using large language models (LLMs) to proactively identify false positive patterns as well as detection gaps (Identify being the keyword, humans should always be in the decision-making loop) should be in place.

Organizations at this level of maturity have a stable, scalable, and reliable capability to detect some advanced threats.

DEMM-5: Threat intel, Threat Hunting, and Purple Teaming generating rules

DEMM-5 indicates that other detection strategies, such as Threat Intelligence, Purple Teaming, and Threat Hunting, have gained enough maturity to where they are generating useful detection rules.

The synergy between different detection strategies indicates the detection capability of the organization has matured enough to where multiple capable layers of strategic defenses exist. This level of maturity should also mean that the detection capability of the teams involved would organically continue to mature as a result of lessons learned, gaps identified, and intelligence acquired over time.

It should also be noted that this level of maturity is incomplete without incident responders providing intelligence to the Threat Intelligence team and collaborating with threat hunters and purple teamers to operationalize lessons learned and detection opportunities identified by those strategies.

At this level of maturity, the ability of the organization to detect the majority of advanced threat actors is a product of the amount of time this level of maturity has been maintained as well as the continued retention of skilled personnel.

DEMM-6: Optimal log collection and detection capability with coverage for all enterprise environments

What sets apart DEMM-6 from DEMM-5 is that log collection is considered to be optimal and sufficient to allow detection of all known significant threat actor tools and techniques. The security team has also matured to the point that techniques that are new or not-so-well-known are being discovered proactively and operationalized as part of the Detection Engineering process.

The security team at this level of maturity has confidence that security log collection and security tool or platform deployments (e.g., endpoint agents, firewalls, and the like) encompass all assets and resources of the organization.

All of the maturity and capabilities discussed up to DEMM-5 are undone if there are blind spots threat actors can abuse to meet their objectives. This is particularly true for APTs because they are persistent; each time they are detected or prevented, they learn more about the environment.

At DEMM-6, the detection team, and thus the organization, has achieved a level of maturity that allows detection capabilities to be rapidly deployed with confidence that not only can they detect all relevant threats, but they can also reliably continue to do so with full coverage of all protected assets and resources. Defenders should be able to go toe-to-toe against advanced threat actors and persistently defend against their stealthy and persistent attacks.

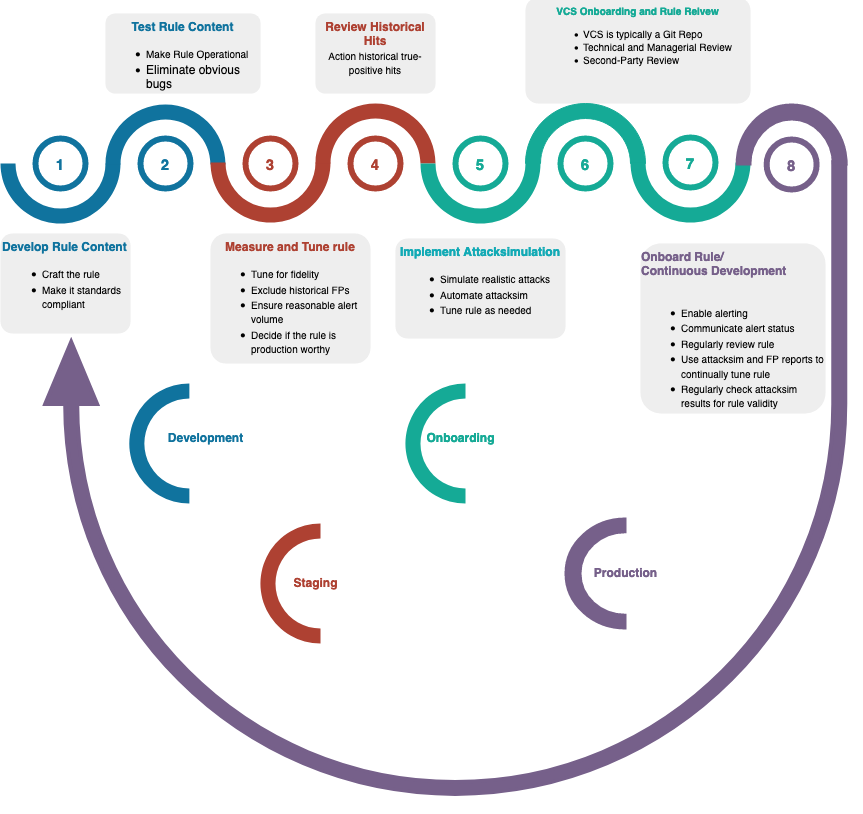

Detection Content Lifecycle

To achieve maturity and develop a detection capability that will allow the detection of advanced threats, detection rule content must be relevant, within acceptable fidelity thresholds, with correct logic, and maintainable.

To achieve these goals, the reference lifecycle below is proposed.

Develop Rule Content

Create the detection logic based on some Threat Intelligence, gap analysis, recent incidents, or purple team exercises. The detection logic should match threat actor activity using available logs and telemetry.

Test, Measure, and Tune the Rule

Execute the rule and ensure that it is functional and works as intended.

Exclude common false positive hits, measure the rule's fidelity, and tune the rule.

Completion of this stage means the alert volume relative to the detection value of the rule is acceptable (high fidelity). Difficulty in investigating alerts for the rule (e.g., resources and time required per incident) should also be considered when tuning a rule. Contextual enrichments, documentation, and investigation guidance can improve the incident handler's investigation experience.

Rules that can't be tuned by excluding false positives might be improved by enriching them with additional context and/or correlating them with other types of logs.

Reasonable compromises should also be made when the rule cannot be made viable by excluding known false positives or by enriching the rule content with more context. This means, for example, not detecting some true positive scenarios would be acceptable if the alternative is not having the rule at all, or having a low-fidelity, high-volume rule. This is in line with a defense-in-depth strategy, where in this context, multiple rules detecting different tactics and stages of an attack combined are expected to compensate for deficiencies in each other.

For example, you may be forced to set a high threshold for network scanning alerts; however, this can be compensated by developing rules that detect exploitation or credential abuse on target hosts or firewalls as one layer, and detecting scanning tools and behavior using endpoint rules (instead of network appliance rules). Even though the network scanning rule is set to a high threshold, attackers who evade it when they scan the network would still have to evade several additional layers of rules to conceal their activities in the network.

Review Historical Hits

Once the rule content is ready for alerting, historical hits that cannot be readily ruled out as false positives (and excluded) should be investigated to see if they are detecting active or historical compromises.

Implement Attack Simulation as part of CI/CD

To ensure that the rule will detect the intended threats, an Attack Simulation should be conducted where possible. If the rule is indeed catching intended threat actor behavior, the Attack Simulation should be automated and integrated with a CI/CD pipeline where it will be used to check the validity and health of the rule. Ideally, the CI/CD pipeline will not simply execute the Attack Simulation but validate the result using integrations with the detection platform to ensure that the rule is firing alerts as intended.

Detection engineers must continually monitor the health status of their rules.

CI/CD pipelines should also continually validate the rule and ensure the rule content is compliant with internal standards (e.g., formatting, documentation, best practices) and ensure that all changes for the rule are tracked as part of a Version Control System (VCS).

VCS Onboarding

A Version Control System such as Git should be used to track changes and collaborate among multiple team members on any updates that will be made to the rule once it is in production. Changes to production rules should document the reason behind the change so that future reviews and audits of the rule can correct past mistakes or update the rule to make it more relevant.

Rule Review

Before detection rules are made to alert incident handlers, a person other than the original rule author should review the rule's quality. This will reduce the number of errors and mishaps caused by one person that resulted in an ineffective or degraded rule.

Detection engineers should also formally review all detection rules using some pre-defined interval. This will not only serve as a check and balance for the initial review, but it will also make sure rules that have poor fidelity, are abandoned, dysfunctional, or irrelevant are addressed.

Enable Rule

New rules can have a significant impact on incident handlers. Some concerns include a lack of understanding of what the rule is aiming to detect or a lack of resources or capabilities the rule author or reviewer may not have been aware of. To avoid this, communication is key.

Especially for high-fidelity rules that rarely fire, when they do fire, incident handlers need to be able to know how to triage these alerts. Communicating new rule onboarding can reduce alert fatigue and incident mishandling for incident handlers.

Aside from that, once a rule is onboarded as a production rule, it should be treated as an important layer of defense against threat actors. As such, when a rule fails to alert or alerts too often, it should be treated as a security control that is in a state of outage or degraded functionality and must be tuned accordingly.

Continuous Rule Development

To maintain their relevance and fidelity, detection rules must be subjects of continuous improvement. While this can include regular reviews by the maintainers of the rule, it should also mean that incident handlers and rule maintainers alike must work to monitor false positives and exclude them.

Continuous development isn't limited to removing false positives. Additional capabilities should be added to rules as gaps and intelligence surrounding the threats that are the subject of the rule are discovered.

Finally, rules should be subject to off-boarding when they become irrelevant, degraded in quality (until quality improves), or too costly to maintain.

Attack-validating Detection Capability

Detection rules provide assurance that when threat actors generate some pattern of activity, alerts will be generated which allow incident handlers to respond to the threat. However, simply defining a rule alone without validating its correctness could result in a false sense of security. Even if a rule is defined correctly, changes in the availability or structure of logs during the lifetime of a rule can result in the rule becoming ineffective or degraded.

A mature Detection Engineering program that is using a Detection-as-Code process can implement CI/CD pipelines where Attack Simulations can be executed continuously for test-validating production rule content. Integrations with the detection platform can then be used to validate the success or failure of the predefined Attack Simulation scenarios.

Best practices

Below are best practices that can be followed to implement an effective Attack Simulation/Validation pipeline.

Multiple attack scenarios

Multiple attack scenarios should be supported to validate one rule. Each scenario could be simulated on a different lab device or environment and have its results validated on the target detection platform.

For example, a rule might detect network scanning activity. One Attack Simulation/Validation scenario might run Nmap in a lab environment where traffic is routed through a specific firewall while another might run Masscan in a production environment. Both scenarios would trigger alerts for one rule; however, they would validate that the rule can detect scanning activity in different environments and with different tools.

Multiple Environments

The larger an organization gets, the more difficult it becomes to maintain a consistent configuration across the environment. This means rules that work well for logs coming from devices and resources in one environment may fail in a different environment.

Not only that, detection engineers often fall into the trap of focusing only on Windows (or whatever the prominent endpoint platform of the organization is) or endpoint alerts; however, other operating systems, firewall alerts, email alerts, cloud alerts, and many more environments must be monitored for threat actor activity. Support for as many current and future monitored environments should be built into any effective Attack Simulation/Validation pipeline. Attack Validation platform support (SOAR, SIEM, data lakes) should also be configurable so that future migrations to different detection platforms would require minimal work to migrate Attack Simulation/Validation configurations.

Unify Attack Simulation and validation configurations

To make maintenance seamless and reduce the amount of work needed to craft Attack Simulation/Validation scenarios, the same configuration that defines what attacks should be executed should also define what fields and alerts on the detection platform would detect that activity.

Attack Simulation/Validation logs

The CI/CD pipeline should log the results of Attack Simulations and validations to a reporting platform where dashboards and alerts can be configured to notify rule maintainers of status changes to rules.

Purple team and Threat Intelligence drive Attack Simulation tuning

Threat actors regularly develop techniques that evade detection rules. This means a rule that is configured to detect a specific technique will be rendered useless if it is too specific. For example, rules that detect a specific command line of an attack tool might stop working if the threat actor adds or removes an extra space or reorders the command-line flags. Attack Simulation scenarios can prevent this if detection engineers continually add attacker techniques and take a purple team approach, where some team members work to evade rule detections while others work to update rules and configure automated Attack Simulation scenarios accordingly.

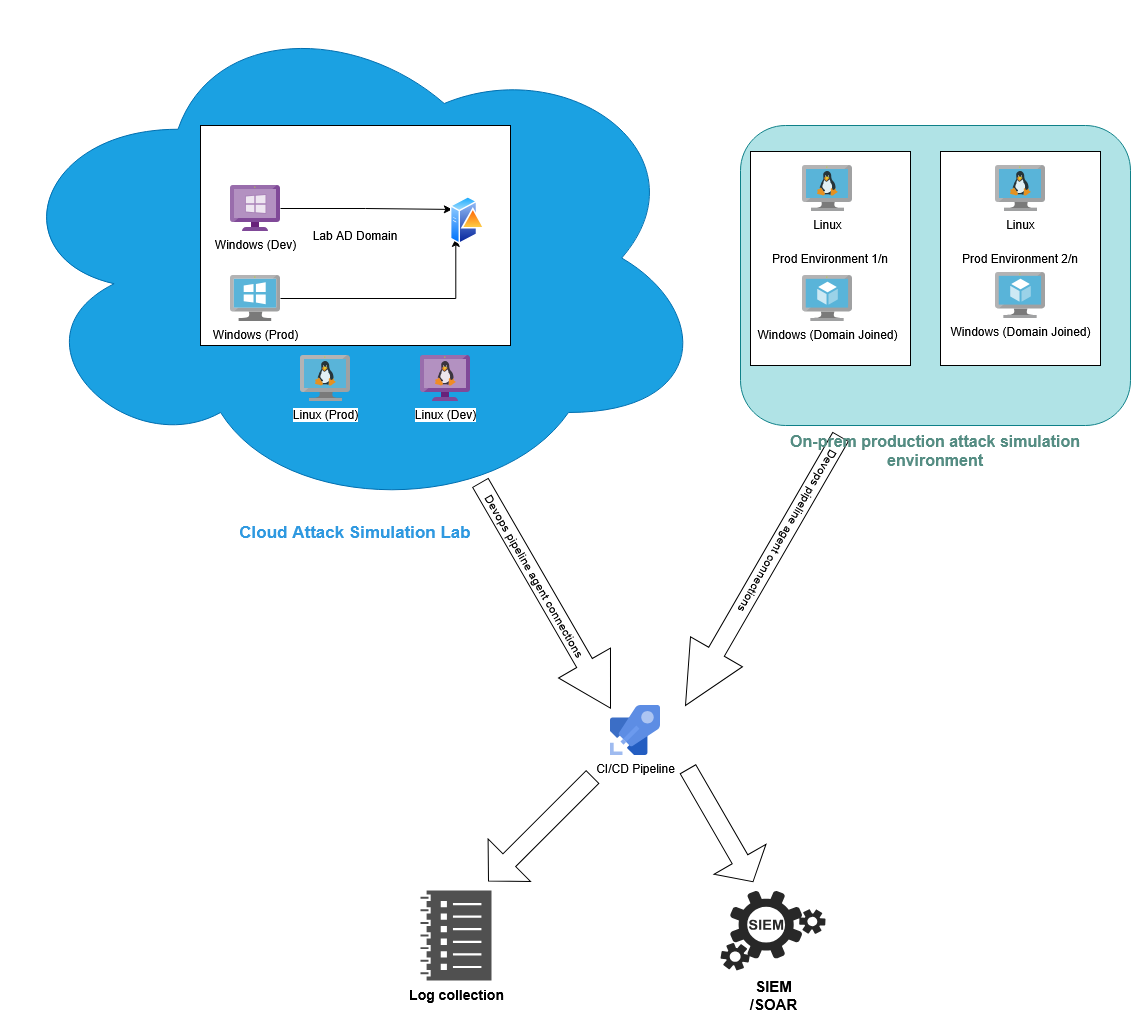

Reference Attack Simulation/Validation pipeline

Below is a diagram of an Attack Simulation pipeline that implements the best practices mentioned earlier in this post

In the reference Attack Simulation/Validation setup, there two Attack Simulation environments:

- Cloud Attack Simulation lab: A lab environment, isolated from the production enterprise systems. Attacks can be tested and tuned in development machines while CI/CD agents execute production Attack Simulations on production machines. The lab environments should execute attacks that don't require specific environmental considerations or that might be too risky and disruptive to production environments.

- Production Attack Simulation environment: Attack Simulations are run under various enterprise systems that have different security controls in place, such as different firewalls, endpoint tools, different Active Directory domains, cloud providers, malware detonation sandboxes, and more. Attack Simulation machines run CI/CD build agents that execute environment-specific Attack Simulations. Production Attack Simulation environments should be integrated into the environment they reside in, this means creating accounts to be used in Attack Simulations, joining the Attack Simulation machines to the production domain, and more.

The CI/CD pipelines should execute whenever new detection content is created or existing detection content is modified.

After enough time has passed for the detection rules being tested to trigger an alert, Attack Validation pipelines should run to search logs in the SIEM/SOAR platform and validate that the attacks were detected or prevented as expected.

The log collection from the CI/CD pipeline execution should report to a detection rule health status reporting and alerting system.

Conclusion

Defending against advanced threats is a competition of resources between an organization and the sponsoring state or criminal organization behind APTs. Different organizations and teams have different resources and risk appetites. Security teams should aim to make the most effective use of the resources at their disposal so that advanced threats will face the most hostile environment when they attack the organization.

In this post, Detection Engineering best practices and a capability-centric detection maturity model have been introduced. Security teams should measure the resources available to them and use the Detection Engineering Maturity Model to gauge the level of readiness they have against advanced threats.

Security teams that have resources at their disposal that permit mature Detection Engineering, Threat Hunting, Purple Teaming, and/or Threat Intelligence programs to be developed should evaluate what their current level of maturity is and how they can achieve a detection posture that is effective against advanced threats.

Specifically for a Detection Engineering program, modern Detection-as-Code practices can be implemented with tools and processes that will allow detection engineers to craft and tune rules that are correct, reliable, and can detect advanced threat actors within their environment.

Lastly, while in this post I've detailed one approach and perspective of winning battles against APTs, it is by no means a definitive work, nor is it without room for improvement. The core strategic take of this post is that victory against APT actors requires maturity which can only be achieved by deliberate, formal and disciplined development of mature capabilities that have the highest cost the organization can impose against its adversaries.